Japan’s 50th House of Representatives elections have been concluded on the evening of October 27, it is not clear whether Shigeru can retain the position of prime minister, but the voter apathy of the political situation has not improved. Turnout in Japan’s smaller districts fell by about two percentage points to 53.85% , the third-lowest since the war, compared with 55.93% in 2021. More worryingly for the Japanese, turnout among the country’s young has long been weak. Some analysts believe that this will further affect Japan’s social governance and“Democratic functioning.”.

Politicians have run their legs off, but turnout remains low

According to Japanese media statistics, during Japan’s 50th House of Representatives election, the heads of nine political parties from the ruling and opposition parties traveled a total of more than 68,000 kilometers during the 12-day election campaign, which could circle the earth one and a half times, but turnout was only 53.85 per cent, only about 1.2 percentage points higher than the lowest since the Second World War, when it was 52.66 per cent in the 2014 House of Representatives election.

Voter turnout in Japan has been low for a long time. The Nihon Keizai Shimbun previously reported that turnout in the country’s lower house elections, which had been around 70 per cent until 1993, fell below 60 per cent for the first time in 1996. In 2009, when the DPJ defeated the LDP in a power transition, turnout in lower house elections (small constituencies) rose to 69.28% , but in 2014,2017,2021 and 2024, turnout was a dismal 56% or less.

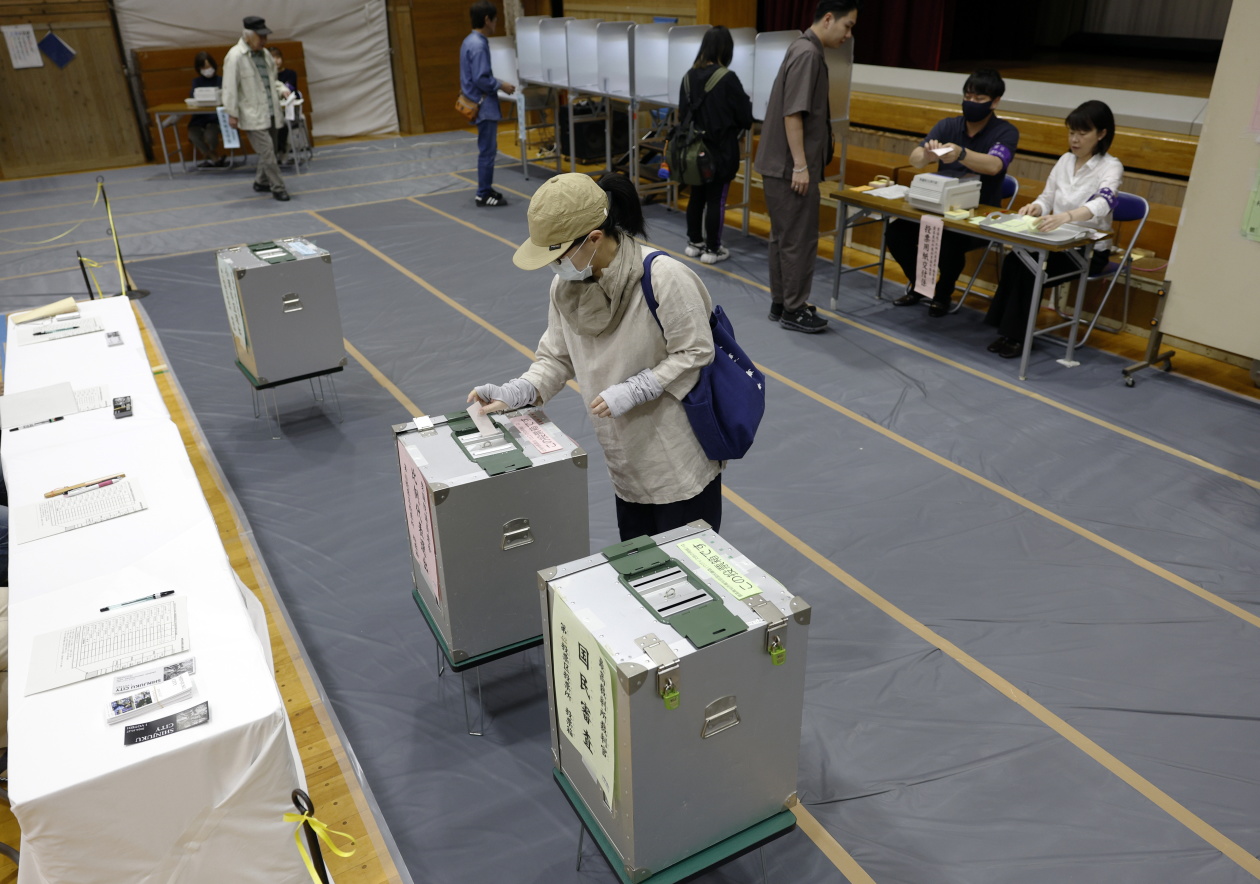

Local time on October 27, Tokyo, Japan, Japan held a house of Representatives election vote.

In contrast to other countries, turnout in Japan was also low. According to Agence France-presse 2021 reported that Japan’s voter turnout in the OECD survey of 41 developed economies in the bottom fifth. According to the International Association for Democracy and Electoral Assistance Data released in 2020, in the national parliamentary elections, Japan’s turnout rate of 53.68% , ranked 139th.

More worrying for Japan than the low turnout is the greater political apathy among younger voters than the electorate as a whole. In 2015, Japan lowered the voting age from 20 to 18. In the 2016 senatorial elections, Japan’s 18-to 19-year-olds turned out in 46.78 percent of the vote. Data released by Japan’s Ministry of General Affairs on October 30 this year showed that in the current house of Representatives election, the turnout of 18-19-year-old groups (small constituencies) preliminary data was 43.06% , that’s about 10 percentage points below the overall turnout. In the 26th senatorial elections in Japan, held in July 2022, the turnout rate of voters aged 18-19 was 35.42 per cent, that of those aged 20-29 was 33.99 per cent and that of those aged 30-39 was 44.80 per cent, all lower than the overall turnout rate of 52.05 per cent, it was also lower than the turnout of these three groups in the 49th House of Representatives elections held in October 2021. At that time, their turnout rates were 43.23% , 36.50% and 47.13% respectively.

The Washington Post’s 2021 report showed that the relative silence of young Japanese about elections and voting stood in stark contrast to the increasingly divisive and polarizing atmosphere in the United States and some European countries. In 2017, about a third of Japan’s eligible 20-to 29-year-old voters cast their ballots in lower house elections. In America the trend is reversed, with under-30s breaking records in both 2018 and 2020.

Global Times reporters also felt the apathy of young Japanese toward politics and elections. When contacted for this article, many declined on the grounds that they“Don’t understand politics” and“Don’t want to talk about politics.”. Lina Sakamoto (not her real name) , a 23-year-old college student with an interest in politics, chose to major in international politics, but she did not vote. “If I’m not asked, I rarely take the initiative to talk about politics,” Sakamoto Lina told the Global Times. “It’s very rare for young people in Japan to talk about politics.” She chose this major purely to satisfy her curiosity, without“Great dreams” such as“Changing Japan” and“Improving national life”.

In his early 50s, Kenichi Morimoto (not his real name) works for a government-related agency. His daughter Reiko Morimoto (not her real name) , who just turned 18, voted in her first election. Reiko Mori told the global times that she went to vote mainly because her family had gone to vote and she wanted to see it. She sees voting in person as an opportunity to learn. So what issues are young Japanese interested in these days? Reiko Mori says she doesn’t know much about this.

Japanese young people do not understand, do not care, do not expect

Some analysts believe that the electoral system, political environment, social and cultural factors in different countries vary greatly, which will have a great impact on the turnout rate. In Scandinavian countries such as Norway and Denmark, which have “Big government”, high benefits and a high burden, citizens think public opinion can be reflected, said Masao Itada, a professor of political Meiji University, so the turnout was high. Japan, by contrast, may not vote because its citizens find it difficult to reflect public opinion in policy.

The Asahi Shimbun 2023 cited a survey in which 48 per cent of eligible voters in the country who rarely or never vote said they did not vote because of a lack of worthy candidates, thirty-six percent said they would“Not change politics or society” even if they voted, while 35 percent said they“Don’t trust politics.”.

For the low turnout in the lower house of Japan elections, there is analysis that this is the LDP supporters of the party’s“Punishment” related. Masao Kudo (not his real name) , 45, voted for the LDP in a Tokyo constituency. In an interview with the Global Times, he said it was not that the LDP was strong, but that the LDP had gone too far and decided from the start that it would never vote for the LDP. As Kudo observes, the fallout from the“Black Gold” scandal is far from over. The LDP’s policies are not the subject of much discussion in Japan, but rather the party’s loss of popular trust. The lack of trust has two main consequences: either vote for parties outside the LDP or not vote at all.

So why are young Japanese reluctant to vote actively? In this regard, AFP analysis published in 2021, said that the outdated campaign strategy and lack of political education, leading to the long-term low turnout of young Japanese two reasons. Many young people in the country are very interested in social issues, but they are often unaware of the differences between political parties, said Yukio Kiyoshi, a member of the non-governmental organization Japan Youth Conference, this is partly because of a lack of voter education in schools, but also because“Parties are not doing enough to reach young people”. Digital petitions and social media have helped revolutionise political life in Japan in recent years, but old-fashioned campaign methods such as speaking at railway stations remain common.

According to a 2019 report by the Nihon Keizai Shimbun, a survey showed that the country’s youth turnout remained low because, besides“Not caring about politics” and“Not having time,” And“Policies that are all for the elderly, and politics that don’t focus on the young”.

In fact, Japan lowered the voting age from 20 to 18 in 2015 in order to avoid the growing influence of the elderly in politics as the phenomenon of aging and fewer children intensifies, that is, to reduce the so-called“Silver-haired democracy” phenomenon. The term “Silver democracy” refers to the gradual increase in the electoral power of older people, with population ageing, to influence political decision-making and the allocation of resources.

Lina Sakamoto told the global times that young people don’t vote because they don’t understand politics, don’t understand because they don’t care, don’t care because they don’t expect, not expecting is because“Nothing changes”. “This is a very important reason,” Sakamoto Lina said. “Why care when you know it won’t solve the problem? Over time, young people feel that politics and policy have little to do with their lives. Even people who know something about politics may not be happy with Japan’s political system,” she said bluntly, japanese politicians“Choose almost anyone”, anyway“Choose no one good”, the difference is only“Bad or worse”, so simply do not choose anyone, do not participate.

Talking about the current political environment and atmosphere in Japan, Sakamoto Lina that there are“Two kinds of Split.”. First, politicians at the top are divided from ordinary people. In a country where money is the basis of election campaigns, zero per cent of politicians are now second or third generations of hereditary politicians, “They grew up in a privileged environment and knew nothing about the suffering of ordinary people, which is why some politicians behave in such a way that people are speechless,” he said. Sakamoto Lina said that the second kind of division is between the city and the local division. People in Tokyo, for example, have relatively high household incomes and access to education, but the opposite is true in places. The two groups live in their own circles, without understanding each other and without the will to know.

The candidate kept repeating three sentences in his campaign

“Young Japanese often feel they have no say in the country’s future,” the Washington Post said. Professor of Japanese Prefectural University of Kumamoto, Dolph Sawada, said politicians would see little point in focusing on the aspirations of the younger generation if turnout remained low, this will eventually lead to a society that is not conducive to the younger generation.

US media reported that the average age of the 465 member of the House of Representatives of Japan elected in October 2021 was 55.5. According to a survey conducted by Katsumoto Ono, a professor of Japanese Waseda University politics, and Maclean’s, a scholar at Yale University, the under-50s accounted for just over 10 percent of candidates in mayoral elections held between 2004 and 2019, less than 20 per cent of candidates for the town council are also candidates.

A 2022 study by Hiroshi Yoshida, a professor of aging economics at Tohoku University, cited by the Asahi Shimbun, said that abstention by the younger generation in elections would affect its economic interests. He defines those under 50 as“The younger generation” and those aged 50 and over as“The older generation”, we also collected voter turnout data for both age groups in Japan’s national elections from 1976 to 2019. According to the study, every 1 percent drop in turnout among voters under 50 in national elections costs them nearly 78,000 yen a year.

Nao taoko, a co-representative of“No youth, no Japan”, a Japanese civil society group that aims to draw young people’s attention to politics, said that young people in the country increasingly do not see politics as a mechanism to solve social problems, yet the absence of young people in politics may only see politicians make more bad decisions.

Sikuang, a 20-year-old Meiji University student, agrees: “If there is no turning point and only the interests of the elderly are satisfied, then we will only continue to move towards recession and political apathy. We need change.”

To persuade more voters, especially the young, to vote, Japan has also come up with ingenious ways. In the voting system, Japan has increased the“Early vote”“Absent vote” and other means, people can go to a designated place to vote early, convenient for those who may be unable to get away on election day. Japan has also invited stars to endorse or shoot promotional posters, videos, such as AKB48 members have called on young people to actively participate in the vote.

In some parts of Japan, local governments have teamed up with local businesses to offer voting incentives. People can enjoy discounts and free coffee in shopping malls, spas, restaurants and other places with voting certificates.

“Is it true democracy to vote for free coffee?” Sakamoto Lina asked. Kudo shared this story with a reporter from the global times. One day, his middle-school son came to him to talk about politics. He said he witnessed the candidates canvassing at the station: for about 10 minutes, the candidate kept repeating three sentences: “My name is so-and-so,”“Please vote for me,” and“Thank you.”. “There’s nothing else, it’s just to look familiar and get people to vote for him,” Kudo said. “This is the ‘democracy’ of Japan today.”

Zhao Hongwei, a Hosei University professor, told the global times that voting in Japanese elections is more about supporting someone than a party, this is particularly true in small constituencies. Most candidates in small constituencies come from local areas, and voters value the human element and don’t pay much attention to their specific policies, which is almost non-existent among young people, “It also reflects the crisis of Japanese democracy.”.

The Nippon Foundation conducted a survey in February asking 1,000 young people (aged 17 to 19) in six countries, including Japan, the US and the UK, “Whether they think their country will get better in the future”, only 15 per cent of young Japanese said yes; 45.8 per cent said yes when asked if they thought their actions would change the country and society. Both rankings are at the bottom of the six.